COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also called the coronavirus pandemic, was a world-wide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). It is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).[1][7][b]

| COVID‑19 pandemic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

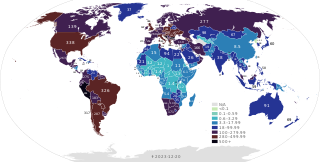

Confirmed cases per 100,000 population

as of 20 November 2022

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

Clockwise, starting from top:

| |||||||

| Disease | Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) | ||||||

| Virus strain | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2)[a] | ||||||

| Source | Probably bats, possibly via pangolins[2][3] | ||||||

| Location | Worldwide | ||||||

| First outbreak | Xiaogan, Hubei, China 30°37′11″N 114°15′28″E / 30.61972°N 114.25778°E | ||||||

| Index case | Wuhan, Hubei, China[4] | ||||||

| Date | 17 November 2019–5 May 2023[4][5] | ||||||

| Confirmed cases | 777,074,039[6] | ||||||

Deaths | 7,079,129[6] | ||||||

The disease was first found in Wuhan, Hubei, China, in December 2019. On 31 December, Chinese health authorities told the World Health Organization (WHO) about a group of viral pneumonia cases of unknown cause,[8] and an investigation was launched in early January 2020.[9] The virus is believed to have come from an animal source, possibly a bat, and it is thought to have been transmitted to humans at a live meat market in Wuhan where live animals were being sold. The virus quickly spread to other parts of the world by airplanes and ships, because of its highly infectious nature and ease of transmission. The World Health Organization (WHO) called it a pandemic (global disease) on 11 March 2020.[10]The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses gave the virus its name. As of September 30 2024, about 777,000,000 cases of COVID-19 have been reported, and about 7,070,000 people have died of COVID-19.[6]

The virus mostly spreads when people are close to each other, which is why social distancing is used.[11] Common symptoms include fever, cough, and trouble breathing.[12] The illness can worsen with pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome.[13] As of January 2021, a number of vaccines for COVID-19 have been developed, but only a few have been found safe to use. The first vaccine to be approved was created by Pfizer and BioNTech,[14] followed by the Oxford / AstraZeneca [15] vaccine. Vaccine distribution was started in many countries in Europe, North America, South America and Asia.[16] The United Kingdom was the first western country to begin to give out a COVID-19 vaccine. [17] The vaccine was given out to all people in the country for free. No antiviral medicine for COVID-19 is available.[18] Doctors usually give patients supportive therapy instead such as giving fluids, food, oxygen, pain relief and other treatments designed to help patients deal with the symptoms.[19] People can avoid spreading the virus by regularly washing their hands, covering their mouth when coughing, maintaining distance from other people, staying away from crowds, wearing medical or cloth face coverings, and being alone for people who think they are infected, also known as quarantining.[18]

The outbreak might be from a coronavirus that usually lives in bats. This then likely infected another animal, possibly a pangolin. It then changed inside that other animal until it could infect humans.[20] It possibly originated at a wet market (a live food animal market), Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.[21] A 55-year-old person from Hubei province was the first human to contract the virus on November 17, 2019.[22] A 61-year-old man who was a regular customer at the market was the first person to die from the virus on January 11, 2020.[23] The exact origin of the virus is still unknown since the market in Wuhan sold a variety of live wild animals in cages. Chinese tourists have spread the virus by traveling to other countries and made it a worldwide pandemic.[24]

Racism and xenophobia against Chinese people and Asians increased during the pandemic.[25]

In November 2020, two companies, Pfizer and Moderna, said they had finished making COVID-19 vaccines. Two mRNA vaccines, one by Pfizer and one by Moderna, have been tested. Both were over 90% effective.[26] Countries began planning to give the vaccine to many people.[27][28][29] 25 other vaccines have been approved by at least one country, and many others are being developed.

The United States has had the most deaths from the virus. Over 1 million Americans have died from the virus.[6]

In May 2023 the WHO announced the end of the public health emergency.

Epidemiology

changeBackground

changeOn 31 December 2019, Chinese health authorities reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) a cluster of viral pneumonia cases of unknown cause in Wuhan,[8] and an investigation was launched in early January 2020.[9]

On 9 June 2020, a Harvard University study suggested that COVID-19 may have been spreading in China as early as August 2019, based on hospital car park usage and web search trends.[30]

Cases

changeCases means the number of people who have been tested for COVID-19 and have tested positive.[31] These cases are according to Johns Hopkins University.

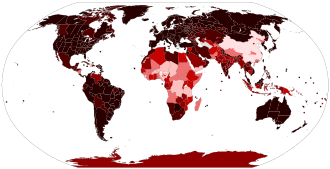

Deaths

changeAlmost all people who get COVID-19 recover. For those who do not, the time between the start of symptoms and death usually ranges from 6 to 41 days, but most of the time about 14 days.[32] This data is recorded by the WHO.

Signs & Symptoms

changeAccording to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 makes people feel sick in different ways, but it usually affects the lungs. People usually cough and have difficulty breathing. They often also have a fever, chills, headache, pain in their muscles, or trouble tasting or smelling things,[34] which can often be confused with the flu virus.[35]

According to an April 2020 study by the American Gastroenterological Association, COVID-19 can make sick people vomit or have diarrhea, but this is rare. They said about 7.7% of COVID-19 patients vomited, about 7.8% had diarrhea and about 3.6% had pain in their stomachs.[36]

Treatment

changeSince there is no exact cure for Covid-19, treatment has focused on treating the symptoms of the disease such as giving oxygen and using machines to aid breathing, giving pain killers to relieve pain, supportive treatment such as giving fluids, food and drugs to combat other symptoms and diseases that affect the person at the same time. Doctors have tried different medicines to see if they help in treatment such as colchicine, systemic corticosteroids (particularly dexamethasone), interleukin-6 receptor antagonists (such as tocilizumab), and Janus kinase inhibitors (such as baricitinib) have been seen to reduce mortality and have other benefits in patients with severe covid-19, such as reducing the severity of the disease and reducing the length of hospital stay.

Data

change-

Map of the COVID-19 outbreak100,000+ confirmed cases10,000–99,999 confirmed cases1,000–9,999 confirmed cases100–999 confirmed cases10–99 confirmed cases1–9 confirmed casesNo confirmed cases, no population, or no data available

| Location | Cases | Deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World[c] | 777,074,039 | 7,079,129 | |

| European Union[d] | 186,326,528 | 1,266,431 | |

| United States | 103,436,829 | 1,210,067 | |

| China[e] | 99,381,428 | 122,389 | |

| India | 45,044,521 | 533,658 | |

| France | 39,008,711 | 168,123 | |

| Germany | 38,437,756 | 174,979 | |

| Brazil | 37,511,921 | 702,116 | |

| South Korea | 34,571,873 | 35,934 | |

| Japan | 33,803,572 | 74,694 | |

| Italy | 26,826,486 | 197,542 | |

| United Kingdom | 25,021,035 | 232,112 | |

| Russia | 24,771,517 | 403,923 | |

| Turkey | 17,004,712 | 101,419 | |

| Spain | 13,980,340 | 121,852 | |

| Australia | 11,861,161 | 25,236 | |

| Vietnam | 11,624,000 | 43,206 | |

| Argentina | 10,110,358 | 130,730 | |

| Taiwan | 9,970,937 | 17,672 | |

| Netherlands | 8,640,582 | 22,986 | |

| Iran | 7,627,863 | 146,837 | |

| Mexico | 7,622,487 | 334,816 | |

| Indonesia | 6,829,949 | 162,059 | |

| Poland | 6,767,469 | 120,967 | |

| Colombia | 6,394,655 | 142,727 | |

| Austria | 6,083,011 | 22,534 | |

| Greece | 5,747,684 | 39,813 | |

| Portugal | 5,670,415 | 29,075 | |

| Ukraine | 5,541,489 | 109,925 | |

| Chile | 5,408,705 | 64,497 | |

| Malaysia | 5,325,669 | 37,351 | |

| Belgium | 4,892,342 | 34,339 | |

| Israel | 4,841,558 | 12,707 | |

| Czech Republic | 4,823,694 | 43,761 | |

| Canada | 4,819,055 | 55,282 | |

| Thailand | 4,806,280 | 34,741 | |

| Peru | 4,528,708 | 220,994 | |

| Switzerland | 4,474,075 | 14,170 | |

| Philippines | 4,173,631 | 66,864 | |

| South Africa | 4,072,857 | 102,595 | |

| Romania | 3,567,404 | 68,949 | |

| Denmark | 3,444,841 | 10,012 | |

| Singapore | 3,006,155 | 2,024 | |

| Hong Kong | 2,876,106 | 13,466 | |

| Sweden | 2,769,633 | 28,283 | |

| New Zealand | 2,661,984 | 4,489 | |

| Serbia | 2,583,470 | 18,057 | |

| Iraq | 2,465,545 | 25,375 | |

| Hungary | 2,237,300 | 49,114 | |

| Bangladesh | 2,051,516 | 29,499 | |

| Slovakia | 1,885,409 | 21,262 | |

| Georgia | 1,864,383 | 17,151 | |

| Republic of Ireland | 1,751,759 | 9,909 | |

| Jordan | 1,746,997 | 14,122 | |

| Pakistan | 1,580,631 | 30,656 | |

| Norway | 1,530,642 | 5,732 | |

| Kazakhstan | 1,504,370 | 19,072 | |

| Finland | 1,499,712 | 11,466 | |

| Lithuania | 1,418,458 | 9,862 | |

| Slovenia | 1,360,964 | 9,914 | |

| Croatia | 1,352,684 | 18,781 | |

| Bulgaria | 1,338,911 | 38,771 | |

| Morocco | 1,279,115 | 16,305 | |

| Puerto Rico | 1,252,713 | 5,938 | |

| Guatemala | 1,250,394 | 20,203 | |

| Lebanon | 1,239,904 | 10,947 | |

| Costa Rica | 1,235,825 | 9,374 | |

| Bolivia | 1,212,156 | 22,387 | |

| Tunisia | 1,153,361 | 29,423 | |

| Cuba | 1,113,662 | 8,530 | |

| Ecuador | 1,078,897 | 36,055 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 1,067,030 | 2,349 | |

| Panama | 1,044,987 | 8,756 | |

| Uruguay | 1,042,389 | 7,692 | |

| Mongolia | 1,011,489 | 2,136 | |

| Nepal | 1,003,450 | 12,031 | |

| Belarus | 994,045 | 7,118 | |

| Latvia | 977,765 | 7,475 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 841,469 | 9,646 | |

| Azerbaijan | 836,492 | 10,353 | |

| Paraguay | 735,759 | 19,880 | |

| Cyprus | 709,396 | 1,497 | |

| Palestine | 703,228 | 5,708 | |

| Bahrain | 696,614 | 1,536 | |

| Sri Lanka | 672,812 | 16,907 | |

| Kuwait | 667,290 | 2,570 | |

| Dominican Republic | 661,103 | 4,384 | |

| Moldova | 650,822 | 12,283 | |

| Myanmar | 643,238 | 19,494 | |

| Estonia | 613,546 | 2,998 | |

| Venezuela | 552,695 | 5,856 | |

| Egypt | 516,023 | 24,830 | |

| Qatar | 514,524 | 690 | |

| Libya | 507,269 | 6,437 | |

| Ethiopia | 501,258 | 7,574 | |

| Réunion | 494,595 | 921 | |

| Honduras | 472,911 | 11,114 | |

| Armenia | 453,040 | 8,779 | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 404,093 | 16,404 | |

| Oman | 399,449 | 4,628 | |

| Luxembourg | 396,674 | 1,000 | |

| North Macedonia | 352,060 | 9,990 | |

| Brunei | 349,972 | 182 | |

| Zambia | 349,892 | 4,078 | |

| Kenya | 344,113 | 5,689 | |

| Albania | 337,196 | 3,608 | |

| Botswana | 330,696 | 2,801 | |

| Mauritius | 329,686 | 1,074 | |

| Kosovo | 274,279 | 3,212 | |

| Algeria | 272,189 | 6,881 | |

| Nigeria | 267,190 | 3,155 | |

| Zimbabwe | 266,399 | 5,740 | |

| Montenegro | 251,280 | 2,654 | |

| Afghanistan | 235,214 | 7,998 | |

| Mozambique | 233,876 | 2,252 | |

| Martinique | 230,354 | 1,104 | |

| Laos | 219,060 | 671 | |

| Iceland | 210,731 | 186 | |

| Guadeloupe | 203,235 | 1,021 | |

| El Salvador | 201,967 | 4,230 | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 191,496 | 4,390 | |

| Maldives | 186,694 | 316 | |

| Uzbekistan | 175,082 | 1,016 | |

| Namibia | 172,556 | 4,110 | |

| Ghana | 172,331 | 1,463 | |

| Uganda | 172,161 | 3,632 | |

| Jamaica | 157,346 | 3,621 | |

| Cambodia | 139,325 | 3,056 | |

| Rwanda | 133,266 | 1,468 | |

| Cameroon | 125,279 | 1,974 | |

| Malta | 123,582 | 1,167 | |

| Barbados | 108,836 | 593 | |

| Angola | 107,487 | 1,937 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 100,990 | 1,474 | |

| French Guiana | 98,041 | 413 | |

| Senegal | 89,318 | 1,972 | |

| Malawi | 89,168 | 2,686 | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 88,953 | 1,024 | |

| Ivory Coast | 88,457 | 835 | |

| Suriname | 82,505 | 1,406 | |

| New Caledonia | 80,203 | 314 | |

| French Polynesia | 79,451 | 650 | |

| Eswatini | 75,356 | 1,427 | |

| Guyana | 74,492 | 1,302 | |

| Belize | 71,430 | 688 | |

| Fiji | 69,047 | 885 | |

| Madagascar | 68,598 | 1,428 | |

| Jersey | 66,391 | 161 | |

| Cabo Verde | 64,474 | 417 | |

| Sudan | 63,993 | 5,046 | |

| Mauritania | 63,879 | 997 | |

| Bhutan | 62,697 | 21 | |

| Syria | 57,423 | 3,163 | |

| Burundi | 54,569 | 15 | |

| Guam | 52,287 | 419 | |

| Seychelles | 51,899 | 172 | |

| Gabon | 49,056 | 307 | |

| Andorra | 48,015 | 159 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 46,864 | 670 | |

| Curaçao | 45,883 | 305 | |

| Aruba | 44,224 | 292 | |

| Tanzania | 43,365 | 846 | |

| Mayotte | 42,027 | 187 | |

| Togo | 39,537 | 290 | |

| Bahamas | 39,127 | 849 | |

| Guinea | 38,582 | 468 | |

| Isle of Man | 38,008 | 116 | |

| Lesotho | 36,138 | 709 | |

| Guernsey | 35,326 | 67 | |

| Haiti | 34,751 | 860 | |

| Faroe Islands | 34,658 | 28 | |

| Mali | 33,180 | 743 | |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 31,765 | 65 | |

| Cayman Islands | 31,472 | 37 | |

| Saint Lucia | 30,231 | 410 | |

| Benin | 28,036 | 163 | |

| Somalia | 27,334 | 1,361 | |

| Solomon Islands | 25,954 | 199 | |

| United States Virgin Islands | 25,389 | 132 | |

| San Marino | 25,292 | 126 | |

| Republic of the Congo | 25,234 | 389 | |

| Timor-Leste | 23,460 | 138 | |

| Burkina Faso | 22,165 | 400 | |

| Liechtenstein | 21,612 | 89 | |

| Gibraltar | 20,550 | 113 | |

| Grenada | 19,693 | 238 | |

| Bermuda | 18,860 | 165 | |

| South Sudan | 18,855 | 147 | |

| Tajikistan | 17,786 | 125 | |

| Monaco | 17,181 | 67 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 17,130 | 183 | |

| Samoa | 17,057 | 31 | |

| Tonga | 16,992 | 13 | |

| Marshall Islands | 16,297 | 17 | |

| Nicaragua | 16,197 | 245 | |

| Dominica | 16,047 | 74 | |

| Djibouti | 15,690 | 189 | |

| Central African Republic | 15,443 | 113 | |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 14,985 | 41 | |

| Gambia | 12,627 | 372 | |

| Collectivity of Saint Martin | 12,324 | 46 | |

| Vanuatu | 12,019 | 14 | |

| Greenland | 11,971 | 21 | |

| Yemen | 11,945 | 2,159 | |

| Caribbean Netherlands | 11,922 | 41 | |

| Sint Maarten | 11,051 | 92 | |

| Eritrea | 10,189 | 103 | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 9,674 | 124 | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 9,614 | 177 | |

| Niger | 9,528 | 315 | |

| Comoros | 9,109 | 161 | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 9,106 | 146 | |

| American Samoa | 8,359 | 34 | |

| Liberia | 8,090 | 294 | |

| Sierra Leone | 7,985 | 126 | |

| Chad | 7,702 | 194 | |

| British Virgin Islands | 7,643 | 64 | |

| Cook Islands | 7,375 | 2 | |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 6,833 | 40 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 6,771 | 80 | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 6,607 | 46 | |

| Palau | 6,372 | 10 | |

| Saint Barthélemy | 5,507 | 5 | |

| Nauru | 5,393 | 1 | |

| Kiribati | 5,085 | 24 | |

| Anguilla | 3,904 | 12 | |

| Wallis and Futuna | 3,760 | 9 | |

| Macau | 3,514 | 121 | |

| Saint Pierre and Miquelon | 3,426 | 2 | |

| Tuvalu | 2,943 | 1 | |

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha | 2,166 | 0 | |

| Falkland Islands | 1,923 | 0 | |

| Montserrat | 1,403 | 8 | |

| Niue | 1,092 | 0 | |

| Tokelau | 80 | 0 | |

| Vatican City | 26 | 0 | |

| Pitcairn Islands | 4 | 0 | |

| Turkmenistan | 0 | 0 | |

| North Korea | 0 | 0 | |

| |||

Name

changeIn February 2020, the WHO announced a name for the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2: COVID-19. It replaced the name "2019-nCoV."[38] "Covi" is for "coronavirus," "D" for "disease," and "19" for the year 2019 – the year it was first detected. They said they did not want the name to have any person, place, or animal in it because people might blame the disease on that place, person, or animal. For example, it did not use the word "Wuhan." They also wanted the name to be easy to say out loud.[39]

Mortality rate of COVID-19

changeAccording to an article in Market Watch dated on February 27, 2020, the overall case mortality rate in China was 2.3%. However, these results might be severely different between different age groups and between men and women. People over the age of 70 experienced a rate of mortality 4-5 times that of the average. Men were more likely to die than women (2.8% versus 1.7% for women) possibly due to lifestyle, such as it being more possible in men to drink and smoke, making the risk of having a respiratory illness more possible, and thus more vulnerable.[40] These numbers were the conclusion of a study by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention using 72,314 COVID-19 cases in mainland China as of Feb. 11. At that point this was the largest sample of cases for such a study.[41]

On March 5, 2020, the WHO released the case fatality rate.[42]

Race and racism

changeCOVID-19 did not affect everyone in each country the same way.[43] As of May 2020, APM Research Lab said the death rate among black Americans was 2.4 times as high as for white Americans and 2.2 times as high as for Latino and Asian Americans.[44] In July 2020, The New York Times printed data from the Centers for Disease Control showing that black and Latino Americans were three times as likely to become sick and twice as likely to die as white Americans. This was not only in large cities but also in rural areas. This was not only for old people but for people in all age groups. Native Americans were also more likely than whites to become sick and die. Asian Americans were 1.3 times as likely as whites to become sick.[45]

Camara Jones, an epidemiologist who once worked for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said this was socioeconomic and not because of any natural difference in black and white people's bodies.[46] In the United States, black citizens are more likely to work jobs where they serve the public directly and to ride on public transport rather than take their own cars to work. This makes them more likely to be infected than people who work in private offices or from home. Sharrelle Barber, an epidemiologist and biostatistician from Drexel University, also said black Americans can live in crowded neighborhoods where social distancing is harder to do and healthy food harder to find.[47] Both Barber and Jones blamed the long history of racism in the United States for these things. Three senators, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren said the federal government should start recording the race of COVID-19 patients so scientists could study this problem.[47]

In June, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) told the public that people using the United States' government's Medicare health program had different results depending on race. Four times as many black Medicare patients went to hospitals for COVID-19 than white Medicare patients. There were twice as many hospitalized Hispanic patients than white patients. There were three hospitalized Asian patients for every two hospitalized white patients. The head of CMS, Seema Verma, said this was mostly because of socioeconomic status.[48]

In the United Kingdom, twice as many black COVID-19 patients died as white COVID-19 patients. Other non-white people, like people from India and Bangladesh, were also more likely to die of COVID-19 than whites. Britain's Office of National Statistics said that the differences in money and education explained some of this difference but not all of it. They also said they did not know whether non-white patients caught COVID-19 more often or whether they caught more severe cases. Only female Chinese Britons were less likely to die of COVID-19 than white Britons.[49]

Indigenous peoples

changeNative Americans in the United States have shown more deaths from COVID-19 than the rest of the U.S.[50] As of May, the Navajo Nation had 88 deaths and 2,757 cases, and the money they had been promised by the government arrived several weeks late. Only 30% of the people in the Navajo Nation have pipes with running water, which made it difficult for people to wash their hands.[51]

Scientists from Chapman University made a plan to protect the Tsimane people in Bolivia from COVID-19 and said this plan would also work for other indigenous peoples living on their own land. The scientists said that many indigenous peoples have problems that make COVID-19 more dangerous for them, like poverty, less clean water, and other lung diseases. Hospitals may be a long distance away, and racism can affect the way doctors and nurses react. But they also sometimes have things that help, like traditions of making decisions together and the ability to grow food nearby.[50] The scientists found people who spoke the Tsimane language as a first language and made teams to go to Tsimane towns to warn them about COVID-19. They also used radio stations. They said the best plan was for whole communities to decide to isolate. They found this worked well because the Tsimane already usually made their big decisions together as a community in special meetings and already had a tradition of quarantining new mothers. The Chapman scientists said their plan would also work for other indigenous peoples who also make decisions together, like the Tsimane. [50][52] The Waswanipi Cree in Canada, the Mapoon people in Australia, and many groups in South America already tried plans like these on their own.[50][53]

George Floyd protests

changeIn May 2020, police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota killed an unarmed black man called George Floyd while they were arresting him. There were weeks of protests all over the world against police brutality and racism. Experts said they were worried protesters and police could spread SARS-CoV-2 to each other. Other experts said some of the reasons that the protests were so big was because non-white people were being killed by COVID-19 more than white people were, because poor leadership in the COVID-19 crisis reminded them of poor leadership about racism, and because the lockdowns shut down workplaces and other things. This meant people had more time to protest.[53] [54][55][56]

African Americans

changeAfrican Americans are more likely to catch the virus compared to their white counterparts in the United States,[57] and are also more likely to die from it.[58][59] 50,000 African Americans died of COVID-19 in 2020.[60] African Americans are the least likely to get vaccinated against the disease.[61]

Hispanics

changeLatinos have been at a higher risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 in the United States.[62] There are many reasons why Latinos have a higher risk of getting very sick or going to the hospital because of COVID-19. One reason is that they often have health problems like diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. They are also more likely to have jobs where they have to be around other people, like in healthcare, grocery stores, and farming. Many Latinos live in crowded places with many people, like big families or busy neighborhoods. This makes it hard to stay far away from others and can make the virus spread more easily. Some Latinos might not speak English well, which can make it hard to get healthcare or understand how to stay healthy. Finally, many Latinos don't have health insurance or don't have enough of it. All of these things are connected and can make it more likely for Latinos to get very sick from COVID-19.

Conspiracy theories

changeIn early 2020, some people began to think that the SARS-CoV-2 may have been made on purpose in a laboratory and either released by accident or on purpose like a weapon. Some Iranians thought the Americans might have made it.[63] Chinese state media said COVID-19 came from the United States to China and not the other way around.[64] Some Americans thought the Chinese might have made it.[65] Some Britons thought it might have been created by accident by 5G cell phone networks.[66]

On March 17, 2020, scientists from Columbia University and other places published a paper in Nature Medicine showing that SARS-CoV-2 was almost surely not made by humans in a laboratory. They did this by comparing the genomes of different viruses to each other.[20] The scientists saw that SARS-CoV-2 did not match any of the viral backbones that already exist for virologists to use.[67] Within a few weeks, it became one of the most cited scientific papers in history, meaning that other scientists were reading and using it.

There were also several conspiracy theories circulating about Bill Gates and his alleged involvement with the COVID-19 pandemic. Theories wrongfully linking Gates to the coronavirus were mentioned 1.2 million times on television or social media between February and April of 2020.[68] One of the most prominent ones was that Bill Gates somehow created or engineered the virus as part of a plan to depopulate the world. There is no evidence to support this claim, and it has been debunked by numerous experts in the field and fact checking organizations including the the National Institutes of Health[69] and Reuters.[70] Some conspiracy theorists allege that Bill Gates is using the pandemic to profit from the development and distribution of vaccines and other medical treatments. While Gates has been heavily involved in funding research on vaccines and treatments for COVID-19, he has not personally profited from this work. In fact, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has donated over $2 billion to COVID-19 efforts since the start of the pandemic.[71][72]

One of the impacts of these conspiracy theories is that they have generated fear and suspicion towards COVID-19 vaccines.[73] Bill Gates commented on the impact of these theories, saying: "During the pandemic, there were tens of millions of messages that I intentionally caused it, or I'm tracking people. It's true I'm involved with vaccines, but I'm involved with vaccines to save lives."[74]

Graphs

change-

Case fatality rates by age group in China. Data through 11 February 2020.[75]

-

Epidemic curve of daily new cases of COVID-19 (7 day rolling average) by continent

-

Semi-log plot of weekly new cases of COVID-19 in the world and top five current countries (mean with deaths)

-

COVID-19 total cases per 100,000 population from selected countries[76]

-

COVID-19 active cases per 100,000 population from selected countries[76]

-

COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 population from selected countries[76]

Timelines of COVID-19

changeOn December 31, 2019, China alerted WHO to several cases of unusual pneumonia in Wuhan, Hubei province.[77]

On January 20, 2020, Chinese premier Li Keqiang called for efforts to stop and control the pneumonia epidemic caused by a novel coronavirus.[78] As of February 5, 2020, 24,588 cases have been confirmed,[79][80] including in every province-level division of China.[79] A larger number of people may have been infected, but not detected (especially mild cases).[81][82] The first local transmission of the virus outside China occurred in Vietnam between family members,[83] while the first local transmission not involving family occurred in Germany, on January 22, when a German man contracted the disease from a Chinese business visitor at a meeting.[84] As of 5 February 2020[update], 493 deaths have been attributed to the virus since the first confirmed death on January 9, with 990 recoveries.[79][85] The first death outside China was reported in the Philippines, in a 44-year-old Chinese male on February 1.[86] but another source reported: "The first cases of COVID-19 outside of China were identified on January 13 in Thailand and on January 16 in Japan".[87]

There has been testing which have showed over 6000 confirmed cases in China,[88] some of whom are healthcare workers.[89][90]

Confirmed cases have also been reported in Thailand, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, the United States (Everett, Washington and Chicago),[90] Singapore,[91] Vietnam,[92] France[93] and Nepal.[94]

The World Health Organization declared that this is a Public Health Emergency of International Concern since January 30, 2020.

Bloomberg News and other business publications have reported several plant closures, travel restrictions, and imposed quarantines as a result of this outbreak.[95] Many small businesses, even big ones, have gone bankrupt because of the pandemic.

As of February 10, 2020, there have been 40,235 confirmed cases reported of people infected by the virus in China. Also reported were 909 deaths, and 319 cases in 24 other countries, including one death, according to WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.[96]

China

change- The first cases of COVID-19 were detected in Wuhan, Hubei, Mainland China in December 2019.[97]

- On Feb. 4, 2020, the Seattle Times reported that Around 2020 Chinese new year authorities closed down travel from China to Macau. As a result, visits fell eighty percent.[98]

- Feb 6, 2020, the COVID-19 whistleblower, Li Wenliang, dies of the disease.

- On February 6, 2020, according to Chinese authorities, a man from the United States who tested positive for the virus died.[99]

- On February 25, 2020, the Asian Scientist Magazine reported Chinese Scientists Sequence Genome Of COVID-19 [100]

- According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention, China had the largest number of confirmed cases and deaths on March 1, 2020.[101]

- On March 3, 2020, Science (journal) reported:

- China built two new hospitals in one week just for patients of COVID-19

- The article praised the way China has handled this crisis but said "draconian" measures were used to achieve success.[102]

- On March 6, 2020, CNN reported that a hotel used as a COVID-19 quarantine center collapsed. Seventy people were trapped in a collapsed Quanzhou hotel.[103]

- The Chinese economy was greatly affected by the virus, and many factories shut down during the spike of cases in China during the early months of the pandemic.[104]

- As of October 30, 2020, the number of cases of the virus in China were generally going down, with only 771 new cases being reported in the month of October.[105]

United States

change- The first case of COVID-19 in the United States was detected in a man from the state of Washington on January 21, 2020.[106]

- On February 27, 2020, US President Donald Trump appointed Vice President Mike Pence to lead the US response to COVID-19.[107]

- On February 29, 2020, the first death in the US was reported from the state of Washington.[108]

- On March 3, 2020 CBS reported 15 states with confirmed cases.[109]

- Movements such as elbow bumps began replacing handshakes , as handshakes spread the virus and bacteria more.[110]

- On March 6, 2020, the CDC announced that one million test kits would be distributed.[111][112]

- On March 9, 2020, the US stock market was approaching bear territory.[113]

- On March 9, 2020, there were also scattered reports that some were quarantined while their household members were not.[114]

- On March 10, 2020, the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, said that it is was not known how many Americans tested positive for the virus. This was because many of the test kits went out to private companies.[115]

- On March 10, 2020, the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, announced that the city of New Rochelle was the largest cluster of COVID-19 cases in the state. Among other things done to contain the virus in New Rochelle, the National Guard was sent to the city to hand out food and disinfect buildings.[116]

- On March 26, the United States surpass Italy and China's cases, becoming the epicenter for a while.[117]

- On April 3, 2020, the CDC first recommended the use of cloth face coverings by the general public to reduce the spread of the virus in places such as grocery stores and pharmacies.[118]

- On April 11, the U.S. became the most death in the world.[119]

- On July 22, 2020, the United States surpassed 1,000 daily COVID-19 deaths for a second time.[120]

- On September 22, 2020, the United States reached 200,000 deaths from the virus.[121]

- Between September to October, there was a COVID-19 outbreak at the White House, causing many officials to be diagnosed with the infection, including President Donald Trump and First Lady Melania Trump.[122]

- In December 2020, California surpassed over 30,000 new cases in a day.[123]

- On December 11, 2020, the Food and Drug Administration said doctors could give people the Pfizer vaccine.[27][29]

- On December 14, 2020, the State of New York gave people the first vaccines, starting with health care workers.[27][29]

- On December 26, 2020, California had a record breaking 65,055 new cases in a day after Christmas.[124]

- California became the first state to surpass 2 million cases in December 2020.[125]

Economic effects of COVID-19 in the United States

change- On March 6, President Trump signed a $8.3 billion emergency spending package to fight the COVID outbreak.[126][127]

- On March 5, 2020, it was announced that medical costs for Washington state residents asking to be tested would be waived until May.[128] (People have to pay for their own health care in the United States. See: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act).

- On March 9, 2020, President Trump proposed, among other measures, a payroll tax cut to help the US economy.[129]

Italy

change- On February 27, 2020, according to the EU Observer, a dozen towns in the northern regions of Lombardy and Veneto were under lockdown, with around 50,000 citizens not allowed to leave, and over 200 reported cases of COVID n Italy.[130]

- On March 4, 2020, according to the Guardian, the Italian government has ordered the closing of all of Italy's schools and universities until 15 March 2020[131]

- On March 5, 2020, the Guardian reported: "Italian educational institutions close as Covid-19 deaths pass 100"[132]

- On March 8, 2020, Al Jazeera reported that after a daily infection rate of 1,247 cases, Lombardy together with ten other areas were sealed off to try to quarantine 16 million people.[133] The cities of Milan and Venice were in the quarantined area.[134]

- On March 10, 2020, it was reported that Italy was under quarantine.[135][136]

- On October 5, 2020, Italy imposed a new lockdown and set of restrictions after previously relaxing them. This was due to a second wave of cases that was even worse than the one in spring.[137]

Iran

change- On 28 February 2020, the BBC reported COVID-19 deaths in Iran were at least 210.[138]

- March 3, 2020, multiple Iranian government officials including deputy health minister Iraj Harirchi and vice president of women and family affairs Masoumeh Ebtekar, who served as a spokesperson during the Iran hostage crisis, had contracted COVID-19.[139][140]

Canada

change- The first case of COVID-19 in Canada was detected in a man from Toronto on January 25, 2020.[141]

- On March 12, 2020, Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, the wife of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, tested positive for coronavirus. The Prime Minister and his wife isolated for 14 days.[142]

- On April 6, 2020, Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer, Theresa Tam, said that people should use simple cloth facemasks to help slow the spread of the virus.[143]

South Africa

change- The new coronavirus strain, called the 501.V2 Variant, was first discovered in South African province Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape. It spreads more rapidly.[144]

Australia

change- First case reported on 25 January 2020.[145]

- See COVID-19 pandemic in Australia

New Zealand

change- The first case of COVID-19 in New Zealand was detected in late February 2020 in a person in their 60s.[146]

- Between August 25, 2021, and August 31, 2021, the whole of New Zealand had been temporarily increased to its maximum lockdown level, Level 4, due to the delta variant.[147] Most of the cases during August 2021 were originated from New South Wales.[148] As of September 6, 2021, all of New Zealand has dropped to Level 2, while Auckland remains at Level 4.[147]

Cruise ships

change- On the Diamond Princess cruise ship, out of 3,711 total passengers and crew members, 621 people, or 17% of all the people on board the ship tested positive for COVID-19. The ship ended its quarantine on February 18th.[149]

Africa

change- In late February 2020, Nigeria had it's first case in Sub-Saharan Africa which negatively affected Nigeria's economy, education, religion and social relationships.[150]

- In November 2020, Africa surpassed 2 million cases.[151]

Food and hunger

changeThe pandemic made it more difficult for millions of people all over the world to get enough food. People lost their jobs, so they did not have money to buy food. Farms were shut down, so there was less food made. Processing plants and food factories were shut down, so less food was made ready for people to eat.[152]

In April, Arif Husain of the United Nations' World Food Program said that 130 million more people could go hungry, in addition to the 135 million who were already hungry before the pandemic began. He said that poorer countries would be more affected than rich countries because the way they move raw food from farms to cities and other places where people live is less organized and relies more on human beings than on automatic systems.[152]

This hunger crisis is different from crises in other years because it happened to the whole world at the same time. That meant that people working in other countries could not help by sending money home.[152][153]

All over the world, children who ate meals at school had less access to food when the schools were shut down.[152]

Scientists from the University of Michigan said the pandemic was making it harder for people to find food. In a study published in May, they said one in seven Americans over age 50 said they had trouble getting enough food before the pandemic, and it got worse when senior centers that provided meals were closed.[154] Federal and state governments started programs to bring food to older people and children. There were also more food donation drives in towns.[153]

Elderly

changeIn the United States, nursing homes had some of the highest rates of infection and death, with 40% of all COVID-19 deaths in the country. Nursing homes are group homes for old people who need medical care, for disabled people who need medical care, and for people recovering from severe sickness or injury, like stroke patients.

Many people who live in nursing homes pay through the government program Medicaid, which pays less than Medicare or regular insurance companies. In June, many American nursing homes were caught throwing their regular patients out so they could make room for COVID-19 patients who could pay them more. Because nursing homes had stopped allowing visitors, it took longer for them to get caught. United States law requires nursing homes to warn patients 30 days before kicking them out, but the nursing homes did not do this.

Some of the nursing homes took the COVID-19 patients because state governments asked them to and they say they sent their elderly residents away because they were worried, they would catch COVID-19 from the sick patients.[155]

Environment

changeBecause so many governments told people to stay at home, there was less air pollution than usual for that time of year. Pollution in New York fell by 50% and the use of coal in China fell by 40%.[156] The European Space Agency showed pictures taken from a satellite of China's pollution disappearing during quarantine and coming back when everyone went back to work.[157]

The pandemic and shutdowns made people use less electricity. In the United States, people got less of their electricity from coal power but kept using gas and renewable power like wind and solar power. This was because coal plants are more expensive to run, so power companies used them less.[158]

Pollution from before the pandemic also affected what happened after people became sick. Scientists saw that more people died from COVID-19 in places with large amounts of air pollution. One team of scientists from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg looked at air pollution information from satellites and statistics on COVID-19 deaths in Italy, France, Germany and Spain and saw that places with large amounts of nitrogen dioxide pollution had more people die from COVID-19. Nitrogen dioxide can damage the lungs.[159][160]

The shutdowns and social distancing also affected animals. Human beings started staying at home about the same time in the spring when sea turtles like to come on land to lay their eggs. Turtle scientists in the United States and Thailand both reported more nests than usual on seashores in Florida and Phuket. They say it is because people are not coming to the beach or bringing their dogs to the beach and because there are fewer boats in the water nearby. Scientists also say they see more dugong and dolphins.[161][162][163] With fewer cars driving down roads, salamanders, frogs, and other amphibians were able to cross them for their spring migration. According to citizen scientists from Big Night Maine, a group that watches amphibians, four amphibians made it across the roads alive for every one amphibian killed by cars. Most years, it is only two to one.[164]

Not all ocean mammals did well. According to marine biologists in Florida, manatee deaths in April and May were 20% higher than in 2019. They say this was because many people decided to go boating because other things to do were closed.[165]

Stopping the next pandemic

changeResearchers from the San Diego Zoo Global had the idea for a system that people could use to find dangerous germs before they become pandemics or even before they jump from other animals to humans. They said it was important to watch the wildlife trade, like in the Wuhan wet market. The scientists said that over the past eleven years it has gotten easier and easier to sequence viral genomes, and it does not have to be done by a large lab or by a government anymore. The scientists said it would be better to spread the work out among more people.[166][167]

List of terms used in COVID-19 pages

change- Long COVID is the set of symptoms that stay for a long time after getting COVID-19

- SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID-19

- 2019-nCoV is the old name for SARS-CoV-2

- Coronavirus disease 2019 is the complete name for COVID-19

- Community spread is the spread of the disease without a known travel connection

- Clusters are groups of COVID-19 cases in which many people in the same area became infected with COVID-19

References

change- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- ↑ "Coronavirus very likely of animal origin, no sign of lab manipulation: WHO". Reuters. 21 April 2020. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ↑ Lau SK, Luk HK, Wong AC, Li KS, Zhu L, He Z, et al. (April 2020). "Possible Bat Origin of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 26 (7). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): 1542–1547. doi:10.3201/eid2607.200092. ISSN 1080-6059. OCLC 1058036512. PMC 7323513. PMID 32315281. S2CID 216073459.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Novel Coronavirus—China". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ↑ Rigby, Jennifer; Satija, Bhanvi; Rigby, Jennifer; Satija, Bhanvi (2023-05-08). "WHO declares end to COVID global health emergency". Reuters. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Ritchie, Hannah; Mathieu, Edouard; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Hasell, Joe; Macdonald, Bobbie; Beltekian, Diana; Dattani, Saloni; Roser, Max (2020–2023). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2024-12-30.

- ↑ "Coronavirus disease 2019". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Novel Coronavirus". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Mystery pneumonia virus probed in China". BBC News. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ↑ "WHO Director-General's opening 7remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020". World Health Organization. 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ "COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response". UNESCO. 4 March 2020. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020.

- ↑ "Symptoms of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ↑ "Covid: Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine approved for EU states". BBC News. 2020-12-21. Archived from the original on 2021-01-03. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- ↑ "'Safety first': UK health regulatory officials approve Oxford vaccine – video". The Guardian. 2020-12-30. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-12-31. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- ↑ "Which countries have rolled out COVID vaccine?". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-04. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

- ↑ "UK becomes first country to authorize Pfizer/BioNTech's Covid-19 vaccine, first shots roll out next week". CNN. 2 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-01-03. Retrieved 2021-01-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ↑ 18.0 18.1 "FAQ: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". World Health Organization. 12 October 2020. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 University of Sydney (March 26, 2020). "Unlocking the Genetic Code of the Novel Coronavirus: How COVID-19 Made the Leap From Animals to Humans". SciTech Daily. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus 'could have started at market where koala, snake and wolf meat sold'". Daily Mirror. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ↑ "1st known case of coronavirus traced back to November in China". Live Science. 14 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ↑ Taylor, Derrick Bryson (17 March 2021). "A Timeline of the Coronavirus Pandemic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ↑ "How Chinese tourism helped spread the coronavirus". 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ↑ Muhammad, Nylah Iqbal (2020-02-07). "The coronavirus exposes the history of racism and "cleanliness"". Vox. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ↑ Denise Grady (November 16, 2020). "Early Data Show Moderna's Coronavirus Vaccine Is 94.5% Effective". New York Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Richard Pérez-Peña (December 12, 2020). "How the Vaccine Rollout Will Compare in Britain, Canada and the U.S." New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ↑ Benjamin Mueller (December 8, 2020). "As U.K. Begins Vaccinations, a Glimpse of Life After Covid". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 "America begins its most ambitious vaccination campaign". New York Times. December 14, 2020. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus may have been in Wuhan in August, study suggests". 9 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ↑ "Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN (May 2020). "The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak". Journal of Autoimmunity. 109: 102433. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. ISSN 0896-8411. PMC 7127067. PMID 32113704.

- ↑ Julia Naftulin (26 January 2020). "Wuhan Coronavirus Can Be Infectious Before People Show Symptoms, Official Claims". sciencealert.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ↑ "Symptoms of Coronavirus". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ "Influenza (flu) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- ↑ "New COVID-19 guidance for gastroenterologists" (Press release). Eurekalert.org. May 4, 2020. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ Ritchie, Hannah; Mathieu, Edouard; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Hasell, Joe; Macdonald, Bobbie; Beltekian, Diana; Dattani, Saloni; Roser, Max (2020–2023). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2024-12-30.

- ↑ Brett Dahlberg and Elena Renken (February 11, 2020). "New Coronavirus Disease Officially Named COVID-19 By The World Health Organization". NPR. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- ↑ Sanya Mansoor (February 11, 2020). "What's in a Name? Why WHO's Formal Name for the New Coronavirus Disease Matters". Time. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ↑ Bwire, George M. (2020-06-04). "Coronavirus: Why Men are More Vulnerable to Covid-19 Than Women?". Sn Comprehensive Clinical Medicine. 2 (7): 874–876. doi:10.1007/s42399-020-00341-w. ISSN 2523-8973. PMC 7271824. PMID 32838138.

- ↑ Fottrell, Quentin. "Will coronavirus kill you? Why fatality rates for COVID-19 vary wildly depending on age, gender, medical history and country". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 2020-03-02. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ Belluz, Julia (Mar 5, 2020). "Did the coronavirus get more deadly? The death rate, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ Sujata Gupta (April 9, 2020). "Why African-Americans may be especially vulnerable to COVID-19". Science News. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ↑ "The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the U.S." APM Research Labs. May 20, 2020. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ↑ Richard A. Oppel Jr.; Robert Gebeloff; K.K. Rebecca Lai; Will Wright; Mitch Smith (July 5, 2020). "The Fullest Look Yet at the Racial Inequity of Coronavirus". New York Times. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ↑ Edwin Rios (April 9, 2020). "Black People Are Dying From COVID-19 at Higher Rates Because Racism Is a Preexisting Condition". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 John Eligon; Audra D. S. Burch; Dionne Searcey; Richard A. Oppel Jr. (April 7, 2020). "Black Americans Face Alarming Rates of Coronavirus Infection in Some States". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ↑ Maria Godoy (June 22, 2020). "Black Medicare Patients With COVID-19 Nearly 4 Times As Likely To End Up In Hospital". NPR. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ↑ Benjamin Mueller (May 7, 2020). "Coronavirus Killing Black Britons at Twice the Rate of Whites". New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Hillard S. Kaplan; Benjamin C. Trumble; Jonathan Stieglitz; Roberta Mendez Mamany; Maguin Gutierrez Cayuba; Leonardina Maito Moye; Sarah Alami; Thomas Kraft; Raul Quispe Gutierrez; Juan Copajira Adrian; Randall C. Thompson; Gregory S. Thomas; David E. Michalik; Daniel Eid Rodriguez; Michael D. Gurven (May 15, 2020). "Voluntary collective isolation as a best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations? A case study and protocol from the Bolivian Amazon" (PDF). Lancet. 395 (10238): 1727–1734. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31104-1. PMC 7228721. PMID 32422124. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ↑ Chapman University (May 15, 2020). "Voluntary collective isolation is best response to COVID-19 for indigenous populations" (Press release). Eurekalert. Archived from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Javier C. Hernández; Benjamin Mueller (June 1, 2020). "Global Anger Grows Over George Floyd's Death in Minneapolis". New York Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ↑ Brooke Cunningham (June 8, 2020). "Protesting Police Brutality and Racial Oppression Is Essential Work". Time. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ↑ David Robinson; David McKay Wilson; Nancy Cutler; Ashley Biviano; Matt Steecker (June 6, 2020). "Why George Floyd's death, COVID-19 inequality sparked protests: 'We're witnessing history'". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ↑ The Daily Show with Trevor Noah: June 8, 2020 - Miski Noor & Anquan Boldin. Comedy Central. June 8, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ↑ "US blacks 3 times more likely than whites to get COVID-19". CIDRAP. 14 August 2020. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "African Americans more likely to die from coronavirus illness, early data shows". Reuters. Apr 6, 2020. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022 – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ "Black communities account for disproportionate number of Covid-19 deaths in the US, study finds". CNN. 5 May 2020. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ↑ "The Virus is Showing Black People What They Knew All Along". The Atlantic. 22 December 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Weber, Hannah Recht, Lauren (Jan 17, 2021). "Black Americans Are Getting Vaccinated at Lower Rates Than White Americans". Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Noe-Bustamante, Luis; Krogstad, Jens Manuel; Lopez, Mark Hugo (Jul 15, 2021). "For U.S. Latinos, COVID-19 Has Taken a Personal and Financial Toll". Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ Jon Gambrell. "Iran leader refuses US help, citing virus conspiracy theory". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-29. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ↑ Kuo, Lily (March 13, 2020). "'American coronavirus': China pushes propaganda casting doubt on virus origin". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ↑ David E. Sanger (May 3, 2020). "Pompeo Ties Coronavirus to China Lab, Despite Spy Agencies' Uncertainty". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ↑ Poppy Noor (April 13, 2020). "A third of Americans believe Covid-19 laboratory conspiracy theory – study". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ↑ Kristian G. Anderson; Andrew Rambaut; W. Ian Lipkin; Edward C. Holmes; Robert F. Garry (March 17, 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- ↑ Wakabayashi, Daisuke; Alba, Davey; Tracy, Marc (2020-04-17). "Bill Gates, at Odds With Trump on Virus, Becomes a Right-Wing Target". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ↑ Islam, Md Saiful; Kamal, Abu-Hena Mostofa; Kabir, Alamgir; Southern, Dorothy L.; Khan, Sazzad Hossain; Hasan, S. M. Murshid; Sarkar, Tonmoy; Sharmin, Shayla; Das, Shiuli; Roy, Tuhin; Harun, Md Golam Dostogir (2021-05-12). "COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence". PLOS ONE. 16 (5): e0251605. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1651605I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0251605. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8115834. PMID 33979412.

- ↑ "Fact check: Bill Gates is not responsible for COVID-19". Reuters. 2020-09-10. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ↑ "Funding commitments to fight COVID-19". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ↑ "How Bill Gates and partners used their clout to control the global Covid response — with little oversight". POLITICO. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ↑ Stieg, Cory (14 December 2021). "Bill Gates: 'Conspiracy theories that unfortunately involve me' are keeping many Americans from the Covid vaccines". CNBC. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ↑ Vlamis, Kelsey. "Bill Gates said he'd rather fund vaccines to 'save lives' than go to Mars, but he thinks someday Elon Musk will be a 'great philanthropist'". Business Insider. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- ↑ The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) – China, 2020 Archived 2020-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. China CDC Weekly, 2020, 2(8): 113–122.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 "European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control". Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "Timeline: How the new coronavirus spread | Coronavirus pandemic News | Al Jazeera". Archived from the original on 2020-03-08. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- ↑ "Chinese premier stresses curbing viral pneumonia epidemic". China Daily. Beijing: Xinhua News Agency. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 "Tracking coronavirus: Map, data and timeline". BNO News. 10 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ↑ "全国新型肺炎疫情实时动态 – 丁香园·丁香医生". ncov.dxy.cn. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ↑ Imai, Natsuko; Dorigatti, Ilaria; Cori, Anne; Donnelly, Christl; Riley, Steven; Ferguson, Neil M (21 January 2020). "Estimating the potential total number of novel Coronavirus cases in Wuhan City, China (Report 2)" (PDF). Imperial College London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ↑ "HKUMed WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Control releases real-time nowcast on the likely extent of the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak, domestic and international spread with the forecast for chunyun". HKUMed School of Public Health. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ↑ "China coronavirus: 'family cluster' in Vietnam fuels concerns over human transmission". South China Morning Post. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ↑ "Germany confirms human transmission of coronavirus". Deutsche Welle. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ↑ Qin, Amy; Hernández, Javier C. (10 January 2020). "China Reports First Death From New Virus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ↑ Ramzy, Austin; May, Tiffany (2 February 2020). "Philippines Reports First Coronavirus Death Outside China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ coronavirus#citationMax Roser and Hannah Ritchie (2020) - "Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus'[permanent dead link] [Online Resource]

- ↑ World Health Organization (2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 13 (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330778. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-28. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ Lisa Schnirring: WHO decision on nCoV emergency delayed as cases spike Archived 2020-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Field, Field (22 January 2020). "Nine dead as Chinese coronavirus spreads, despite efforts to contain it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ Goh, Timothy; Toh, Ting Wei (23 January 2020). "Singapore confirms first case of Wuhan virus; second case likely". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ↑ "Vietnam confirms first acute pneumonia cases in Saigon - VnExpress International". Archived from the original on 2020-05-30. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ↑ "France confirms two cases of deadly coronavirus". The Independent. 2020-01-24. Archived from the original on 2020-01-25. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ↑ "First case of coronavirus in Nepal after student who returned from Wuhan tests positive". 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ↑ "Hospital Says Chinese Doctor Has Officially Died: Virus Update". Bloomberg News. 5 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2020-02-07.

- ↑ Singh, Shivani; Nebehay, Stephanie (Feb 10, 2020). "Coronavirus cases outside China could spark a 'bigger fire': WHO". National Post. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ James Gallagher (January 18, 2020). "New virus in China 'will have infected hundreds'". BBC. Archived from the original on January 18, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus shuts Macao, the world's gambling capital". The Seattle Times. Feb 4, 2020. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: two deaths in Wuhan thought to be first of foreign nationals". Guardian. January 8, 2020. Archived from the original on April 10, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Chinese Scientists Sequence Genome Of COVID-19". Asian Scientist Magazine. Feb 25, 2020. Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ refname=ecdc

- ↑ "China's aggressive measures have slowed the coronavirus. They may not work in other countries". www.science.org. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "10 dead after coronavirus quarantine hotel collapses in China". CNN. 7 March 2020. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ↑ Mistreanu, Simina. "China's Factories Are Reeling From Forced Coronavirus Closures". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "China - COVID-19 Overview - Johns Hopkins". Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Archived from the original on 2020-10-29. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ↑ "1st confirmed case of new coronavirus reported in US: CDC". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2020-10-29. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "Trump appoints Pence to lead US response to COVID-19". www.healio.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "US Reports First Death From COVID-19". Medscape. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Coronavirus kills 6 in Washington state". www.cbsnews.com. 3 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-05-17. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ Davies, Caroline (2020-03-03). "Elbow-bumps and footshakes: the new coronavirus etiquette". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "Trying to make up for lost time, the CDC will distribute 1.1M COVID-19 tests by this weekend". TechCrunch. 7 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-05-27. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Jankowicz, Mia. "The White House says it will fail to meet its goal of providing enough coronavirus test kits for 1 million people by the end of the week". Business Insider. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "A devastating day leaves the Dow only 210 points from bear market territory". Fortune. Archived from the original on 2020-12-07. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Newman, Andy (2020-03-09). "Confusion Over Coronavirus Quarantines Feeds Anxiety". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-11-14. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "Health and Human Services chief says 'we don't know' how many Americans have been tested for coronavirus". CNN. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ↑ Nir, Sarah Maslin; McKinley, Jesse (2020-03-19). "'Containment Area' Is Ordered for New Rochelle Coronavirus Cluster". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Wang, Yanan (2020-03-27). "U.S. COVID-19 caseload surges to most in the world". Coronavirus. Archived from the original on 2021-01-11. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

- ↑ "Recommendation Regarding the Use of Cloth Face Coverings | CDC". 2020-04-03. Archived from the original on 2020-04-03. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Hernandez, Nicole (12 April 2020). "U.S. Has Most Coronavirus Deaths In The World". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2021-01-10. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

- ↑ Aratani, Lauren; agencies (2020-07-22). "US daily coronavirus deaths surpass 1,000 for first time since June". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-11-19. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "'Unfathomable': US death toll from coronavirus hits 200,000". AP NEWS. 2020-09-22. Archived from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Buchanan, Larry; Gamio, Lazaro; Leatherby, Lauren; Keefe, John; Koettl, Christoph; Walker, Amy Schoenfeld (2020-10-08). "Tracking the White House Coronavirus Outbreak". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-10-07. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "California has its most coronavirus deaths in a single day as cases, hospitalizations continue to surge". Los Angeles Times. 9 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/california-coronavirus-cases[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "California Becomes First State to Surpass 2 Million Covid-19 Cases". 25 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-12-25. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ↑ Choi, Matthew. "Trump calls Inslee a 'snake' over criticism of coronavirus rhetoric". POLITICO. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Florida confirms two deaths, first outside West Coast". NBC News. 7 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-03-07. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ↑ "Kreidler orders Washington health insurers to waive deductibles, coinsurance and copays for coronavirus testing | Washington state Office of the Insurance Commissioner". www.insurance.wa.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "Trump proposes payroll tax cut, other measures to offset coronavirus economic damage". NBC News. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ "No risk yet to Schengen from Italy's coronavirus outbreak". EUobserver. 25 February 2020. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Italy orders closure of all schools and universities due to coronavirus". the Guardian. Mar 4, 2020. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Italian educational institutions close as Covid-19 deaths pass 100 – as it happened". the Guardian. Mar 5, 2020. Archived from the original on May 7, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ Mohamed, Kate Mayberry,Ramy Allahoum,Hamza. "366 coronavirus deaths in Italy, Saudi schools shut: Live updates". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Coronavirus: Northern Italy quarantines 16 million people". BBC News. Mar 8, 2020. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "'Load of malarkey': Manitobans trapped in Italy lockdown not worried about COVID-19 outbreak". Winnipeg. Mar 10, 2020. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ Belluz, Julia (Mar 10, 2020). "Italy's coronavirus crisis could be America's". Vox. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ Mellen, Ruby. "Italy imposes harshest coronavirus restrictions since spring lockdown as second wave sweeps Europe". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Iran's deaths at least 210, hospital sources say". BBC News. Feb 28, 2020. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Expediency Council member Mohammad Mirmohammadi dies". Tehran Times. March 2, 2020. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ↑ Nasser Karimi; Jon Gambrell (March 2, 2020). "Virus ravaging Iran kills confidant of its supreme leader". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Here's a timeline of COVID-19 cases in Canada". Global News. Archived from the original on 2020-11-16. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "Sophie Grégoire Trudeau tests positive for coronavirus | CBC News". CBC. Archived from the original on 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "Theresa Tam offers new advice: Wear a non-medical face mask when shopping or using public transit". Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "New Covid-19 mutant found in South Africa spreads more swiftly". WION. December 24, 2020. Archived from the original on December 28, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ↑ "First confirmed case of novel coronavirus in Australia". Australian Government Department of Health. 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ↑ www.ETHealthworld.com. "New Zealand confirms first case of coronavirus: health ministry - ET HealthWorld". ETHealthworld.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 "History of the COVID-19 Alert System". Archived from the original on 2021-09-06. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

- ↑ "Covid-19: A timeline of the Delta outbreak". 23 August 2021. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ↑ "Transmission of the novel coronavirus onboard the Diamond Princess". The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-11-16. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ Ajibola, Colins (14 May 2020). "AFTERMATHS OF THE CATASTROHIC COVID-19 ANYWAY FORWARD FOR AFRICAN GOVERNMENTS? NIGERIA AS A CASE STUDY". Gong News. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "Covid-19: Africa surpasses 2 million cases". 19 November 2020. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ↑ 152.0 152.1 152.2 152.3 Abdi Latif Dahir (April 22, 2020). "'Instead of Coronavirus, the Hunger Will Kill Us.' A Global Food Crisis Looms". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 Sanford D. Bishop; Nita M. Lowry (May 10, 2020). "Opinion: The coronavirus crisis is a food security crisis too". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ↑ University of Michigan (May 11, 2020). "Even before COVID-19, many adults over 50 lacked stable food supply" (Press release). Eurekalert. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ↑ Jessica Silver-Greenberg; Amy Julia Harris (June 21, 2020). "'They Just Dumped Him Like Trash': Nursing Homes Evict Vulnerable Residents". New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ↑ Martha Henriques (March 27, 2020). "Will Covid-19 have a lasting impact on the environment?". BBC. Archived from the original on April 10, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ↑ Jeff McMahon (March 22, 2020). "New Satellite Video Shows China Pollution Vanishing During COVID-19 Lockdown—Then Coming Back". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 9, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ↑ Brad Plumer (May 13, 2020). "In a First, Renewable Energy Is Poised to Eclipse Coal in U.S." New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ↑ Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg (April 20, 2020). "Corona and air pollution: How does nitrogen dioxide impact fatalities?" (Press release). Eurekalert. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ↑ Yaron Ogen (July 15, 2020). "Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as a contributing factor to coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality". Science of the Total Environment. 726: 138605. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.72638605O. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138605. PMC 7151460. PMID 32302812.

- ↑ Tricia Goss (April 29, 2020). "Sea Turtles Are Thriving Now That Humans Are Stuck Inside". SimpleMost. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ↑ Kristen Chapman (April 14, 2020). "Experts say coronavirus concerns could have positive impact on marine life". CBS. Archived from the original on April 29, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ↑ Jack Guy; Carly Walsh (April 20, 2020). "Sea turtles thriving in Thailand after beach closures". CNN. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ↑ Brandon Keim (May 18, 2020). "With the World on Pause, Salamanders Own the Road". New York Times. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ↑ Cheryl Rodewig (June 29, 2020). "Florida manatee deaths up 20 percent as Covid-19 threatens recovery". Guardian. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ↑ San Diego Zoo Global (July 9, 2020). "Researchers call for worldwide biosurveillance network to protect from diseases" (Press release). Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ↑ Mrinalini Watsa (July 10, 2020). "Rigorous wildlife disease surveillance". Science. 369 (6500): 145–147. Bibcode:2020Sci...369..145W. doi:10.1126/science.abc0017. hdl:20.500.11820/e98ae7a8-9311-4499-bb1f-4e74b81efec9. PMID 32646989. S2CID 220428903. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.